Trans-Gulf of Mexico Migration

Tony Celis-Murrillo, Tara Beveroth, and the rest of the crew work with tower installation in the Yucatan Peninsula overlooking the Gulf of Mexico.

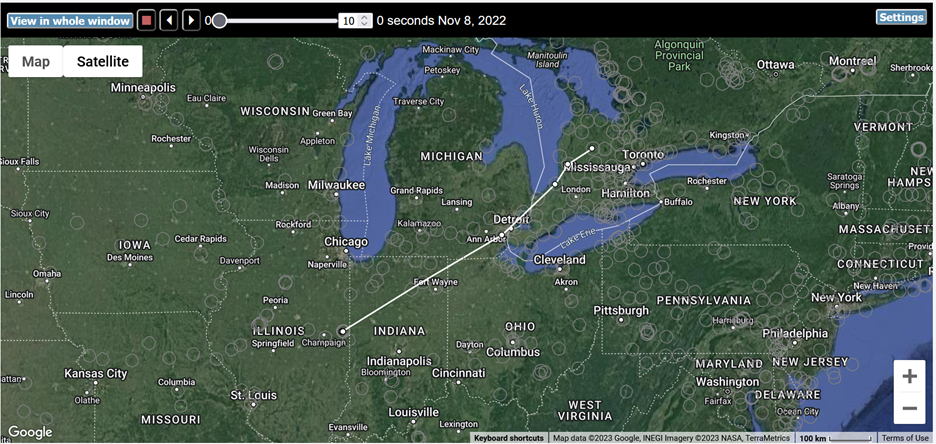

Twice a year millions of birds migrate across the Gulf of Mexico on their way to and from their wintering and breeding grounds. While a 1000 km non-stop flight across a large water body may (or may not) be a significant obstacle, no other research has tracking small individual birds across the gulf with the precision to determine how long it took them to cross the gulf, how weather conditions may impact their journey, and simply whether or not they were able to survive the crossing.

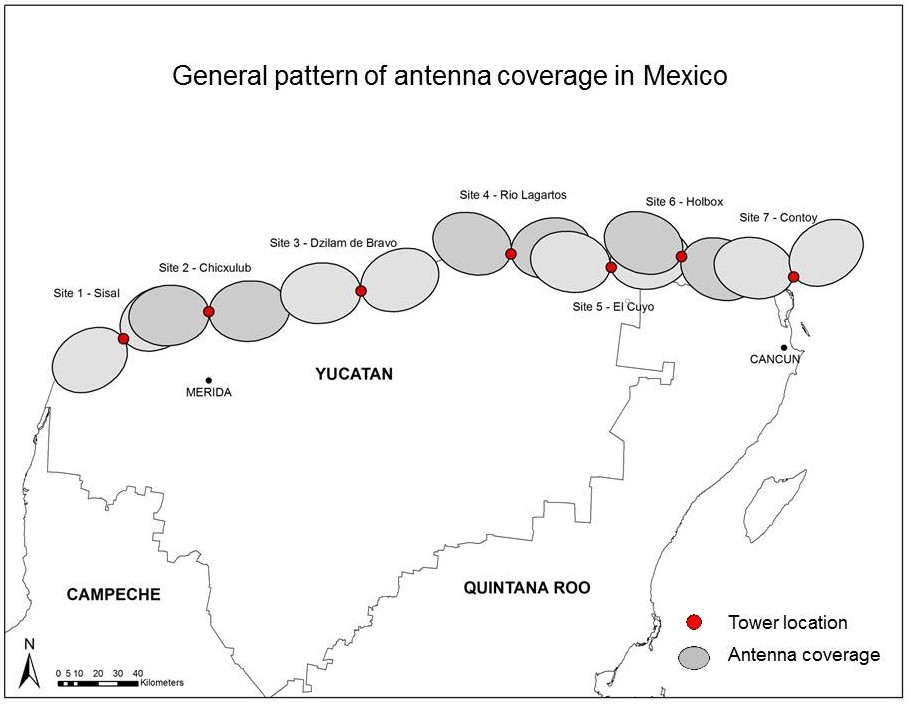

In collaboration with Dr. Jill Deppe (Eastern Illinois University), Dr Robb Diehl (University of Southern Mississippi/USGS), Dr. T.J. Zenzal, Dr. Rachel Bolus, Dr. Frank Moore (University of Southern Mississippi), Dr. Antonio Celis-Murillo, and Dr. T.J. Benson (INHS), and we used automated radio telemetry units to create a radio telemetry fence across the northern tip of the Yucatan Peninsula to investigate the migratory behavior of birds crossing the Gulf of Mexico. This research was funded by the National Geographic Society and is currently funded by the National Science Foundation. We found that most individuals can cross the 1000 km in less than 24 hours and that a combination of wind direction and body condition (fat levels) predicts much of their departure behavior and the ability to successfully cross the Gulf of Mexico.

Some of the papers produced via this research include:

- Ward, M. P., T. J. Benson, J. L. Deppe, T. J. Zenzal, R. H. Diehl, A. Celis-Murillo, R. Bolus, and F. R. Moore. 2018. Estimating apparent survival of songbirds crossing the Gulf of Mexico during autumn migration. Proceeding of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.285: 20181747.

- Schofield, L. N. J. L. Deppe, T. J. Zenzal, M. P. Ward, R. H. Diehl, R. T. Bolus, and F. R. Moore. 2018. Using automated radio telemetry to quantify activity patterns of songbirds during stopover. The Auk: Ornithological Advances 135: 949-963.

- Zenzal, T. J., F. R. Moore, R. H. Diehl, M. P. Ward, and J. L. Deppe. 2018. Migratory hummingbirds make their own rules: factors influencing the decision to resume migration along an ecological barrier. Animal Behavior 137: 215-224.

- Schofield, L. N., J. L. Deppe, R. H. Diehl, M. P. Ward, R. T. Bolus, T. J. Zenzal, J. Smolinsky, and F. R. Moore. 2018. Occurrence of quiescence in free-ranging migratory songbirds. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 72: 36.

- Bolus, R., R. H. Diehl, F. Moore, J. L. Deppe, M. P. Ward, J. Smolinsky, and T. J. Zenzal. 2017. Swainson’s thrushes do not show strong wind selectivity prior to crossing the Gulf of Mexico. Scientific Reports 7:14280.

- Deppe, J. L., M. P. Ward, R. H. Diehl, A. Celis-Murillo, R. Bolus, T. J. Zenzal, F. Moore, J. Smolinsky, L. Schofield, D. Enstrom, E. Paxton, G. Bohrer, T. J. Benson, T. Beveroth, D. Delaney, and W. Cochran. 2015. Fat, weather, and date affect migratory songbird’s departure decisions, routes, and time it takes to cross the Gulf of Mexico. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112: E6331-E6338.

Over the last year TJ Zenzal, and his team have been attaching transmitters to migrants in the fall at Fort Morgan Peninsula in Alabama to determine when and in what direction they depart. An array of seven automated receiving units with high-gain antennas was installed to create a telemetry fence across the northern shores of the Gulf of Mexico from Port St. Joe, Florida to Pearl River, Louisiana. An active hurricane season in 2020 hindered data collection efforts, but further research is anticipated in the coming seasons.

Motus Network

As part of the telemetry initiative of the Midwest Migration Network, we are better trying to understand airspace conservation, stopover behavior and ecology, and phenology as it relates to migratory birds in the Midwest.

To do this, the group has made expanding the Motus network across midwestern states like Illinois a priority. The Motus Wildlife Tracking System is an international collaborative network of researchers that use automated radio telemetry to simultaneously track hundreds of individuals of numerous species of birds, bats, and insects. The system enables a community of researchers, educators, organizations, and citizens to undertake impactful research and education on the ecology and conservation of migratory animals. When compared to other technologies, automated radio telemetry currently allows researchers to track the smallest animals possible, with high temporal and geographic precision, over great distances. Much more about Motus can be found HERE.

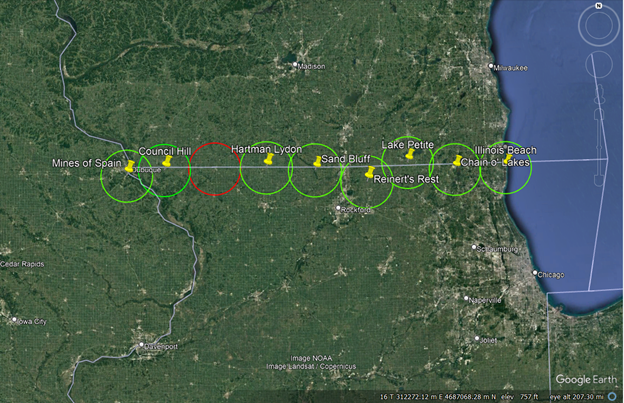

In 2020, the lab–through the support of a grant–worked to install eight radio telemetry towers across a latitudinal line in Illinois to help increase the detection of tagged birds in the Midwest (Motus Region 3). This has expanded such that at present, the lab maintains a total of 20 stations. Six of these stations area a part of a fence of antennas every 15-20 miles across the Illinois-Wisconsin border to track boreal migrants as they migrate north or south. Sites include:

- The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (Urbana, IL)

- Allerton Park and Retreat Center (Monticello, IL)

- Kennekuk County Park (Danville, Illinois)

- A cluster of four towers in the Illinois River valley located near Emiquon National Wildlife Refuge will be utilized for telemetry research with waterfowl and rails at Forbes Biological Station.

- Banner Marsh State Fish & Wildlife Area (Canton, IL)

- Dixon Waterfowl Refuge (Hennepin, IL)

- Illinois Beach State Park (Zion, IL)

- Chain o’ Lakes State Park (Spring Grove, IL)

- Reinert’s Rest (Poplar Grove, IL) — collaboration with McHenry County Audubon

- Sand Bluff Bird Observatory (Rockton, IL)

- Hartman Lydon Wildlife Sanctuary (Orangeville, IL)

- Council Hill (Galena, IL)

Over 200 tags have been deployed on birds (Northern Saw-whet Owl, Sora, Virginia Rail, Brown-headed Cowbird) over the past few years in just Illinois alone. Some tags have lifespans of one year while others may have lifespans of a couple years. Many other tags are deployed every year on other species outside the state. All of these tags have the potential to be detected by towers in Illinois—especially during spring or fall migrations. Two large collaborative projects will involve mass deployments of tags in the next two years (250+ Northern Saw-whet Owl and 600 Wood Thrush) across the full ranges of these species.

Understanding bird migration and movement patterns more generally allows us make better informed and effective conservation decisions. It allows us to better protect migration corridors as we can help minimize mortality risks to heavily trafficked areas. It also helps us understand what breeding and wintering habitats should be protected—especially for sensitive species and those in decline.

While technology has increased what we can do to track bird movement and behavior in recent years, one major barrier to furthering the field is the weight of transmitters that can be placed on a bird. We have been able to place transmitters that collect GPS locations and transmit them via cellular data plans to the internet, but these transmitters are costly and cannot be safely or ethically affixed to birds smaller than 100 grams in most cases. However, smaller radio transmitters can safely and ethically be affixed to these smaller birds. The caveat is that it is necessary to have a tower/antenna near the path the bird travels in order to detect the bird’s location and obtain information about when/where/how the bird is migrating. This has led to the formation of the Motus network and the concept of our northern fence that would increase the likelihood of a bird being detected as it moved north or south into or out of the state.